This article appeared in the March 11, 2022 issue of Above The API, my roundup of the must-know stories in tech. Click here to see the rest.

Few stories in tech have loomed larger in recent months than the troubles befalling the world's largest social media platform, Facebook. Since last fall, the company has been engulfed in turmoil catalyzed by whistleblower Frances Haugen's Facebook Files, which appeared in the Wall Street Journal in late September. The company's subsequent name change to Meta, reflecting a hard pivot to own the next generation of the internet, was likewise met with widespread scorn shortly thereafter.

The true magnitude of Meta's troubles, however, wasn't clear to most until February 2, when the company released its latest quarterly earnings statement. Although nearly three billion people still use its platforms – Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger – daily, the company offered weak forward-looking earnings guidance, sending its stock plummeting nearly 50%.

More interesting than the company's share price, however, is what Meta can teach us about who actually holds the power in our digital economy. In this piece, we'll take a deep dive into digital advertising, eCommerce, and privacy regulations to tease out the root causes of Meta's current troubles, contrasting them with the decidedly rosier prospects for another tech giant, Amazon.

A Framework for Trouble

As it has evolved from a nearly-bankrupt afterthought to the world's most valuable corporation over the past two decades, Apple's annual developer event – the Worldwide Developer Conference, or WWDC – continues to capture increased media attention and cultural relevance with each passing year. WWDC 2020 was no exception: Apple used the event to announce several huge initiatives including Apple Silicon, the company's groundbreaking effort in semiconductor design.

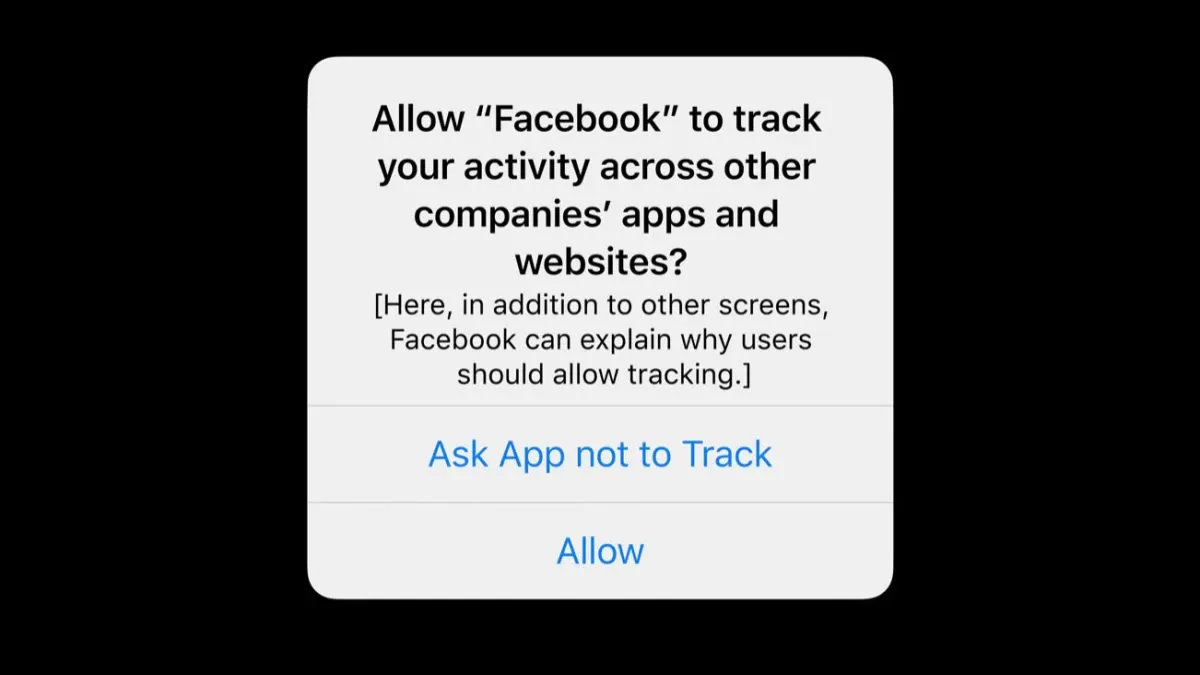

While Apple's new chips and iOS 14 widgets made headlines following the event, an announcement which went unnoticed by most began setting off alarm bells across the digital advertising world: the company would soon roll out a new iOS framework, App Tracking Transparency (ATT), which promised users more control over how apps use and share their personal data. While few outside of ad tech knew it at the time, the entire digital economy, and every buyer, seller, and marketplace contained therein, were likely to be profoundly disrupted.

Nearly two years later, ATT has proven to be just as deserving of headline coverage as Apple's silicon innovations. The framework hasn't just presented Meta with its most existential threat to date: it has fundamentally altered the power structure of Silicon Valley, and by extension, our digital world.

Digital Advertising 101

If you noted a figure I threw out earlier – Meta's stock losing more market capitalization than the collective value of Uber, Spotify, AirBnB, Coinbase, Twitter, Pinterest, and Snapchat combined – you'd be justified in asking a very rational question: just how exactly does Facebook make that much money anyway?

The short answer, historically, is something called Direct Response advertising (DR). Direct Response is, broadly speaking, quite different than traditional print, out-of-home (OOH), or TV advertising. The former seeks to produce a direct and measurable response from viewers, such as visiting a website and purchasing a pair of jeans; the latter is typically focused on brand awareness and general purchase consideration.

When Gucci buys a splashy full-page spread in GQ or a billboard in Times Square, the goal is more to stay top-of-mind and increase brand affinity than drive an instant purchase – although they certainly won't complain if you do so. When a Direct to Consumer (D2C) brand like Warby Parker places a Direct Response ad in your Instagram feed, however, they want one thing: for you to click and purchase that stylish pair of tortoise-shell frames immediately.

This contrast in advertising mediums is even more apparent with purely digital goods. Ever notice how you don't see many ads for mobile games when you're looking anywhere other than at your smartphone? There's a very good reason for that: Facebook's Direct Response model allowed developers to precisely measure how effective their advertising was at driving app installs, calibrating marketing spend with precision against conversion data. Advertising Candy Crush on a billboard, by comparison, seems archaic given the limited conversion metrics available to the advertiser.

You might have noticed a fundamental dependency in the DR model: it doesn't work if the result of an ad impression (the action a user did or didn't take after ad exposure) is unknown. And it is this vital detail that leads us into the story of how Apple kneecapped Mark Zuckerberg's empire.

IDFA Rules Everything Around Me

In the last section, I glossed over a critical part of Meta's now-troubled advertising model: the Warby Parker ad you saw on Instagram wasn't shown randomly, but rather because Facebook inferred from a plethora of data that you're likely in the market for a sleek set of frames. And for years, this playbook was a modern-day gold mine;

- Leverage network effects to sign up millions, and then billions, of users.

- Collect copious amounts of data on each user, building a profile of interests, likes, and a social graph of connections.

- Offer an advertising platform that allows granular targeting based on these user profiles.

This system, along with Google Search, fundamentally reconfigured the advertising landscape across both digital and analog domains, allowing the two companies to capture nearly 55% of all digital ad spend. Advertisers – whether a sprawling multinational corporation or a neighborhood mom-and-pop store – could reach the right user, at the right time, and measure the outcome with precision.

Regardless of your thoughts on digital advertising and its ability to micro-target users, the technological systems deployed to make this entire process work are staggering. In the 1990s, a brand advertiser might call a salesperson at CBS, schmooze a bit, ask about the family and kids, and place an order to run a single ad creative during an upcoming episode of 60 Minutes. Now, billions of mobile devices ping servers across the globe, setting off real-time auctions for ad impressions with zero human intervention; the winning creative then travels near the speed of light through fiber-optic cables and 5G antennas back to a smartphone, where it appears in front of a specific user in mere seconds.

The infrastructure behind this system has two clear challenges. First, how does Facebook know which mobile device is yours – and not one of the other six billion smartphones in use around the world – to deliver that ad in the first place? Second, how can the company know if you end up converting – taking the desired action, whether downloading an app or buying those shades – if that conversion happens outside of a Facebook-owned property?

These two essential components of the iOS digital ad ecosystem were, for years, powered by a string known as the Identifier For Advertisers (IDFA) – a series of 32 alphanumeric characters, such as EA7583CD-A667-48BC-B806-42ECB2B48606 – which is unique to each iOS device. Crucially, Facebook didn't store a user's IDFA in isolation; the identifier became part of your profile, along with other personal data, such as your name, phone number, and web browser cookies.

Pairing the IDFA with ancillary user data unlocked Facebook's advertising dominance at scale. The practice made it possible to identify a user across nearly any website or app, even if a conversion event happened on a property not owned by Facebook, such as the iOS App Store or warbyparker.com:

And then, on that warm summer day in 2020, Tim Cook took the stage at WWDC and threw a wrench the size of California into Facebook's finely oiled advertising machine: Apple would no longer allow app developers unfettered access to users' advertising identifiers.

🍎 Apple Giveth, and Apple Taketh Away

Prior to this change, Facebook's data-driven ad model wasn't merely a boon for the exploding ranks of D2C brands ranging from Casper to Gymshark: it likewise drove spectacular, paradigm-shifting results for app developers, particularly those making mobile games.

On the front-end of the ad journey, Facebook was able to leverage its unparalleled user data to connect an advertiser to the ideal user, using the ad creative most likely to drive conversion. On the back-end, the company used a mix of its own tracking pixel (an invisible image embedded on millions of websites) and mobile advertising identifiers to measure exactly which of those ads converted which users, creating a virtuous cycle of data and targeting enrichment. Over time, Facebook could deliver better non-intent based* results for advertisers than anyone else on the market. Each conversion only made the algorithm just that much better incrementally, but incremental progress adds up when the sample size gets into the billions.

*What Is Intent-Based Advertising?

Google Search, Facebook's historical rival in the digital ad ecosystem, offers a prime example. If I go to Google and search "golf courses near me", it doesn't take a giant leap of engineering to suppose that perhaps the search engine should show me some golf-related ads alongside my results. An even more intent-based query is one where a consumer is explictly looking for a product, such as "best microwave 2022." With some exceptions, Facebook doesn't have Google's advantage of intent-based queries (which make it much easier to predict what someone wants), so the company's algorithms must instead deduce consumer wants and interests from historical data, ancillary signals, and recent browsing history.

To understand how exactly Apple broke Facebook's ad juggernaut, it's helpful to consider the difference in IDFA access before and after this policy change went into practice. Before Apple's changes, individual users' IDFA's were, for the most part, readily available to any iOS developer once an app was installed and launched; the exception to this rule were users who had manually toggled a Limit Ad Tracking setting in their iOS preferences, which relatively few did. After the change went into effect, however, each application on a user's device was required to obtain manual consent before gaining IDFA access, with predictable results: most users opted out. Whereas iOS developers typically had access to advertising identifiers for 70% or more of their users before the change, they are now lucky to have access to 20-30%, if that.

Apple's announcement, therefore, presented an existential risk to Facebook's data-driven model. Because Direct Response advertising relies on measuring the precise outcome of an ad impression – known as deterministic attribution, because the result is determined – losing the IDFA, the crucial identifier powering mobile conversion measurement, blew the whole thing to bits.

Not content to stop there, however, Cook had another trick up his sleeve. Apple simultaneously announced that in addition to heavily restricting IDFA access, developers would be unable to target users who opt out of tracking using any data collected via third parties. This key detail – which many analysts missed – would prove to have enormous consequences for our digital economy in due time.

To understand why, we need only look as far as the recent financial results for another tech giant: Amazon, the unquestioned leader in global eCommerce.

The Everything Store

A proper exploration of how Amazon transformed itself from a scrappy upstart book retailer in Seattle to a global $2T technology juggernaut is well beyond the scope of this article. I'd highly recommend Brad Stone's superb The Everything Store and Amazon Unbound for those wanting to learn more: today, we'll stick to the basics concerning the company's recent ascent in digital advertising.

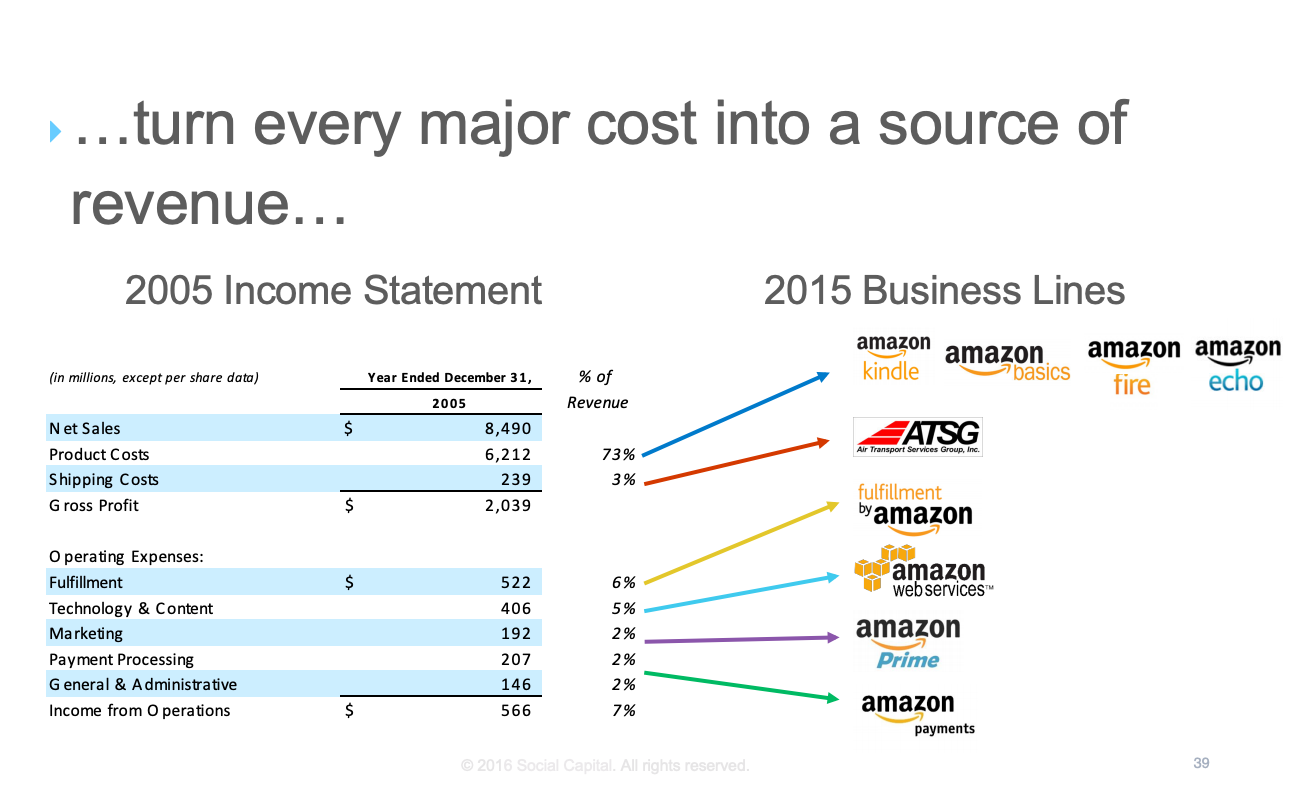

There are many remarkable aspects to Amazon's relentless growth over the past 27 years; chief among them is the perpetual drive to turn its largest expenses into profit centers in their own right. In a now-famous slide from a 2016 analysis of the company's rise, Chamath Palahapitya of Social Capital noted that Amazon had managed to turn nearly every substantial cost on its 2005 earnings statement into a profitable, company-owned business line just one decade later:

In the intervening six years since this analysis, Amazon launched another business line aimed at turning a former margin-destroyer into a profit center: Amazon Advertising, which just so happens to be particularly relevant to our analysis of Meta. If you're interested in learning more about the growth of this aspect of Amazon's business – and the staggering ~$30 Billion in revenue it now generates annually – Trung Phan wrote an excellent recent piece on this here. As Phan notes, Amazon now owns an ad product that generates more annual revenue than that of Snap, Pinterest, and Twitter combined – and managed to build it during a time of significant disruption in the mobile ecosystem due to Apple's IDFA changes.

How is it possible that Amazon's ad product is aggressively scaling revenue year over year while Meta's ad fortunes are in disarray? The answer lies in the fundamental difference between each company's role in the tech ecosystem and how users interact with them.

Location, Location, Location

As I noted earlier, many media outlets missed a crucial nuance buried in Apple's IDFA announcement;

To date, Meta and Amazon have offered two very different user journeys with regard to advertising and commerce. First, consider Facebook's model:

- A user opens the Facebook iOS app;

- Facebook uses its trove of user data to make a highly educated guess about which advertisement (out of millions) it should show;

- Facebook's guess is correct! The user clicks the Warby Parker ad, which takes them to www.warbyparker.com, or the Warby Parker app.

- The user buys the sunglasses.

Next, let's consider the same advertiser buying through Amazon's ad product:

- A user opens the Amazon iOS app;

- Amazon uses its trove of user data to make a highly educated guess about which advertisement (out of millions) it should show;

- Amazon's guess is correct! The user clicks the Warby Parker ad, which takes them to a listing for Warby Parker shades within the Amazon app.

- The user buys the sunglasses.

Given the same user, it should be clear what the fundamental difference is – Amazon's conversion event happens on-platform while Facebook's conversion event happens off-platform.

Armed with our knowledge of Apple's privacy changes, we can now understand why this distinction is so critical: because the entire user journey described here happens on Amazon-owned properties, the company is free to use every bit of data regarding the user's ad exposure and conversion for future targeting, as well as power deterministic attribution* for the brand that purchased the ad.

*Definition: Deterministic versus Probabilistic Attribution

As I've noted, Deterministic Attribution refers to an ad platform's ability to determine the outcome of an ad impression and potential subsequent conversion. By contrast, Probabilistic Attribution – usually a euphemism for the more invasive sounding 'fingerprinting' – offers the advertiser a best guess at whether or not the ad made a user convert. This latter form of attribution, which many advertising networks have scrambled to set up in the wake of Apple's changes, is by definition less precise than its deterministic cousin.

Meta, by contrast, is hamstrung: it is usually blind as to whether or not the ad made a user convert, due to the conversion event happening on a website/app owned by a third party, not Facebook itself.

Given those two options, which platform are you choosing if you're selling a product? As it turns out, the old real estate maxim that 'location is everything' still applies in the digital domain – only now, the question isn't one of physical proximity, but one of URLs and app bundles.

It's also worth noting the impact Apple's changes have wrought on the off-platform advertising networks of both companies. Many of the ads you see in mobile apps not owned by Meta or Amazon are, in fact, powered by those very companies. This is made possible via two ad networks, Amazon TAM and Facebook Audience Network (FAN), which pipe ads sold by each company into third-party apps around the globe. While the location of the ad opportunity may have changed from our prior example – you might see a FAN or TAM ad in a news app that has nothing to do with either company – the consequences of Apple's changes remain the same. As a platform where comparatively few conversion events occur, Facebook remains at a profound disadvantage.

The reason I believe this story warrants a deep dive isn't to explore the nuances of the digital ad market, although this alone has real consequences: remember that advertising powers the free internet. Rather, while the first-order effects of this paradigm shift are noteworthy in their own right, it's the second-order effects they've produced in the tech ecosystem that will be far more impactful on our digital future.

That's So Meta

Given this understanding of Meta's current predicament, we can now better contextualize several related stories you've likely heard about in the tech and financial press recently.

If you've wondered why Meta is relentlessly pushing its first-party eCommerce products – Instagram Shop, Facebook Shops, and Facebook Marketplace – you now have your answer. If you're an avid Instagram user, you've likely been perplexed by the app's incessant redesign, which has one clear goal: placing Instagram Shop at the heart of the user experience. Meta knows it must emulate the Amazon model, where ad targeting and product purchase all tie back to first-party, not third-party, data; a failure to do so will mean a further deterioration of revenue.

Likewise, Shopify's recent struggles – the company's stock is down nearly 70% from last November – owe to the same root cause. For years, Facebook was a prodigious driver of conversions for D2C brands selling via Shopify, propelling the company to a significant share of U.S. eCom revenue. If you've ever been curious as to why, exactly, the social media era aligned with every third person you know starting a bedding, apparel, or supplement brand, now you know. Facebook's unparalleled ad targeting and measurement, when combined with Shopify's turn-key eCommerce platform, made selling D2C goods manufactured by a third party something akin to a science. Because the two companies are separate entities, however, conversion data can no longer be shared as openly between the two in Apple's post-IDFA era. This is leading to higher advertising prices for Shopify merchants, less reliable conversion measurement, and many of the major customer acquisition headwinds currently roiling the D2C economy.

Amazon's model – what I like to call the eCommerce OS (Operating System) – is also helpful in understanding an even larger meta-trend. If you've been trying to comprehend Facebook's sudden pivot to the Metaverse – a computing paradigm that may be a decade away from fruition – the lessons learned here are likewise instructive. While Facebook's existential struggle to redefine its mission owes to no single cause, a major factor in this shift is the company realizing that it must own a more fundamental layer of our digital world – the operating system;

- Apple owns iOS, the mobile operating system used by nine in ten American teens. The company is also developing next-generation augmented reality computing platforms.

- Google owns Android, the mobile OS used by everyone who isn't using iOS – billions of users around the globe. The company also owns the world's most powerful search portal, and is also developing next-gen computing platforms.

- While Amazon does not technically own an operating system, I believe it does in a less traditional sense. As we've explored today, the company not only owns the most powerful eCommerce marketplace in the world; it likewise can reach, convert, and measure shoppers in almost any digital environment thanks to on and off-platform advertising.

Meta, despite its scale, owns relatively little in comparison. The company's apps ride on top of Apple or Google's operating systems, meaning they are subject to the whims of both – as Tim Cook has been all too happy to demonstrate. In the eCom arena, Marketplace continues to be a 'store of last resort' for most consumers. I recently bought an XBox on Marketplace only after being unable to find one in stock literally anywhere else on the internet; I met a stranger inside a Manhattan Chase Bank branch with cash, after furtively calculating if the bank guard would come to my rescue in the event of a transaction gone bad, and no guarantee I'd walk away with a working game console (the XBox works fine, if you're wondering). Hardly an ideal shopping experience!

As a result, Mark Zuckerberg is going all-in on a metaverse-powered future for his company, in hopes that any transition to the world's next computing paradigm will allow Meta to own a more fundamental layer of our digital world. If the company can pull this off, the impact would be transformative; a future in which you stroll through a virtual shopping mall owned by Facebook would offer Meta heaps of first-party data, and the ability to set the rules for its use.

Despite the doom and gloom around Meta, it's worth noting the company has been written off more than once before: those who know it best insist it's a whole different animal when on war footing. Time will tell if Zuckerberg achieves his goal; our present (non-virtual) reality, however, shows how troubled his company will likely be if he's unsuccessful in doing so.

Further Reading

1. Shopify stock is down 50% over the past 12 months. Its mission may be to "arm the rebels," but it is giving us muskets in a war that is increasingly being fought with machine guns.

— Moiz Ali (@moizali) February 16, 2022

👇👇👇